The usual textbook economics involves a lot of mathematics and graphs concerned with maximizing a consumer’s expected utility. If you have ever come across them, you have also probably wondered about the irrationality of the rational choice theory. No consumer has ever drawn a single graph to make purchase decisions between their choices for apples and oranges. In fact, a lot of times we do end up with decisions that are neither in our self-interest nor do they maximize our utility or satisfaction. Behavioral Economics is the study of the influence of social and emotional factors on the decision-making of a consumer. It, thereupon, explains why people make irrational decisions. This blog discusses the utility function and traces the problems with the assumptions in textbook economics towards an introduction to behavioral economics.

What is Utility?

In layman’s terminology, the utility is satisfaction. It measures your satisfaction upon consuming a combination of goods and services. In textbook economics, the rational choice theory assumes that a consumer strives to maximize her utility. Thus, it helps to understand why a rational consumer makes certain decisions based on her utility function. An aggregate estimation of a good’s utility (and that of its substitutions) explains the demand for the good, and thereupon, determines the price. In practice, it is impossible to measure a consumer’s utility in numbers.

Introduction to Behavioral Economics

Behavioral Economics, as a field of economics, emerged in the 1990s. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky (1979), two psychologists, did an experiment to explain the irrational nature of consumers. It helps to begin with their experiment and the Prospect Theory for a layman’s introduction to Behavioral Economics.

Consider, for instance, you are offered a coin toss. If it turns head, you win $2000. If it’s tail, you only lose $1000. Some simple calculations will tell you that the expected earning (calculated as, probability of turning head * gain amount – probability of turning tail * loss amount) is $500. Since the expected earning is positive, you as a rational consumer must go for it. Kahneman and Tversky showed otherwise and came to develop what is called loss aversion.

In their experiment, most people were hesitant to accept the bet even when the expected earning was positive. They explained it with our irrational behavior of loss aversion, whereby, we tend to avoid losses more than we pursue gains. In textbook economics, loss aversion is irrational since it assigns different weightage to an equal amount of gain v. loss.

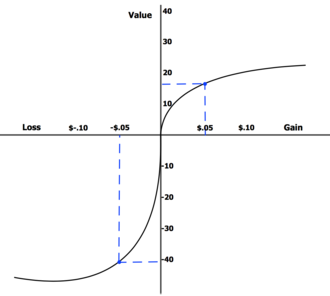

Figure 1 represents this anomaly, whereby, the expected value (read, utility or happiness) from a gain of $0.05 is 20 against a negative utility of 40 for a loss of the same amount. Therefore, this value function graph confirms that consumers tend to maximize their value (utility) function. However, it changes the perspective from which to look at this function.

Further Behavioral Economics

Behavioral Economics challenges textbook economics in another important manner. The origin in figure 1 is the reference point unique and subjective to each consumer. Plus, this reference point changes with personal factors and external influences. These personal factors and external influences have remained a major subject within Behavioral Economics and are a topic for further discussions on behavioral economics in some next blog.

For further reading on behavioral economics, please refer to the two excellent books as followed.

- Levitt, Steven D. & Dubner, Stephen J. Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything. Or, purchase a Kindle edition.

- Akerlof, George A. & Shiller, Robert J. Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism. Or, purchase a Kindle edition.

If you found this helpful, we suggest you read our introduction to insurance as well.